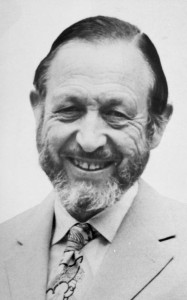

We sometimes contemplate doing something out of the ordinary to celebrate a landmark birthday. For C Warren Bonython AO, to celebrate his 75th, it was to head off to Africa and climb Mount Kilimanjaro. He got within 1700 feet of the summit of this 18,500 feet giant before altitude sickness set in.

Warren was born in Adelaide and his name is synonymous with bushwalking in South Australia. He has however walked extensively in a number of different parts of the world. He began bushwalking while living in Melbourne during the 1940s, heading out into the Dandenong Ranges, and then north into the Cathedral Ranges, with his wife Bunty at his side. Perhaps it was the experience of climbing a challenging ridge on a stormy day, gale-force winds buffeting them with horizontal rain, that decided Bunty against continuing to walk in her husband’s boot prints, or maybe it was their first-born baby waiting at home with her sister. Whatever the reason, Bunty was happy to support Warren in his adventurous life by providing moral support, looking after their three children, and ‘keeping the home fires burning’ while he tramped through far-afield landscapes, including walking the length of the McDonnell Ranges, the Larapinta Trail and Lake Eyre in the Northern Territory; Northern India to the border of Kashmir; and the Sierra Club’s annual high trek in Nevada. He climbed the mountains of Maui and walked through the craters. He first visited New Zealand in 1935 and of course, has done the Everest Trek. Then there was his Simpson Desert walk, 2500 kms, which he shared in his book Walking the Simpson Desert.

Warren was born in Adelaide and his name is synonymous with bushwalking in South Australia. He has however walked extensively in a number of different parts of the world. He began bushwalking while living in Melbourne during the 1940s, heading out into the Dandenong Ranges, and then north into the Cathedral Ranges, with his wife Bunty at his side. Perhaps it was the experience of climbing a challenging ridge on a stormy day, gale-force winds buffeting them with horizontal rain, that decided Bunty against continuing to walk in her husband’s boot prints, or maybe it was their first-born baby waiting at home with her sister. Whatever the reason, Bunty was happy to support Warren in his adventurous life by providing moral support, looking after their three children, and ‘keeping the home fires burning’ while he tramped through far-afield landscapes, including walking the length of the McDonnell Ranges, the Larapinta Trail and Lake Eyre in the Northern Territory; Northern India to the border of Kashmir; and the Sierra Club’s annual high trek in Nevada. He climbed the mountains of Maui and walked through the craters. He first visited New Zealand in 1935 and of course, has done the Everest Trek. Then there was his Simpson Desert walk, 2500 kms, which he shared in his book Walking the Simpson Desert.

Much closer to home Warren took part in the inaugural Hahndorf Pioneer Women’s Trail Walk in 1980 when, with a huge marrow strapped to his back in honour of the pioneers, he joined 150 others on the walk from Hahndorf to Beaumont.

But Warren hasn’t always relied on his walking boots as his preferred mode of travel. In his younger days he moved at a faster pace, owning the first MG sports car in South Australia and setting the speed record on Sellicks Beach. This was a stark contrast to his first major bushwalking venture. Warren had read an article on the Gammon Ranges which stated that no white man had ever penetrated the centre of these ranges. This was the catalyst for him getting a group of people together to make his first attempt. The trip however didn’t go as planned, with one of the party, Bob Crocker, falling and breaking his leg. In 1947 another attempt was made, with the group crossing the ranges from South to North. The following year Warren crossed from East to West.

Warren’s first trip to the Flinders was in October 1945, taking the train from Melbourne and heading out from Brachina, just north of Mount Hayward. His passion for the Flinders was sparked by a painting of Mount Patawarta by Sir Hans Heysen. In his book Walking the Flinders Ranges Warren writes:

“Land of the Oratunga! – the ring of that romantic title and the vision of the magical mountain had drawn me to the Flinders in the first place, and later had helped in inducing me to embark on the walk. I had read of Mount Patawarta while studying Howchin’s “Geology of South Australia”, so I already knew it to be rocky eminence and a commanding viewpoint, and then I had seen the reproduction of Heysen’s painting which had imprinted a separate image in my mind, but it was not until the 1945 Aroona Valley trip that I first actually saw it, instantly equating the two images and recognizing my dream mountain.”

Warren had known Sir Hans for 30 years, and he and Bunty had dined with him at The Cedars, his residence just out of Hahndorf, which is a glorious place still ‘home’ to the artist’s descendants, and now open to the public.

When Warren finally climbed his dream mountain in 1968 Sir Hans was in his early 90s and in hospital. Warren writes:

“On 3 July Charles McCubbin and I had climbed Mount Patawerta, coming down by the south face, and as I had looked back up at the Land of the Oratunga scene my mind suddenly switched to Heysen.”

He wondered later whether this was mental telepathy as Sir Hans had passed away the previous day. Warren wrote of his friend:

“His creative life had ended, but there are appropriate memorials to him in the many paintings in public galleries, boardrooms and private homes, and in the several books about him, and to me there seems none more fitting than that rendering of Patawerta the image of which I permanently carry in my mind’s eye.”

But Warren was to be the instigator of an even more well-known memorial to this great Australian painter – the naming of the Heysen Trail in his honour. In the following year he suggested at a National Trust symposium that there was scope for a long distance walking trail in the manner of the 3,200 km Appalachian Trail in America and the 400 km Pennine Way in England. He had initially considered such a trail through the Mount Lofty Ranges, but having completed his Flinders trek the year before, covering the full length of the Ranges in a number of stages, he put forward a combination of both.

It was fortunate that the Hon. Murray Hill, MLC, had attended the symposium and he approached Government with the idea. This resulted in the formation in early 1970 of the Long Distance Trail Committee, of which Warren was a member, becoming Chairman for the last seven years of its existence. It was in discussion of an appropriate name for the trail that ‘Heysen’ was decided upon because of the artist’s perfecting of the gum tree in the Mount Lofty Ranges and who had then ‘brought the glories of the Flinders Ranges to the world’s notice’. Warren wrote that although he wasn’t a formal bushwalker, ‘Heysen could be a most energetic walker in pursuit of his work.’

Warren was to be the instigator of an even more well-known memorial to this great Australian painter – the naming of the Heysen Trail in his honour.

Much to Warren’s disappointment the Long Distance Trail Committee was disbanded in 1978, and he took time out and headed off overseas to trek in the Himalayas. He had however laid the ground work – paved the way for others, especially Terry Lavender, to continue to develop the Trail. Since that time Warren has officiated at the commissioning of various sections and continues his close association through the Friends, being the association’s long term and revered Patron.

Warren’s career highlights are many. He achieved his BSc. from the University of Adelaide, later going on to work in the chemical industry with ICI Australia 1940-66, including 20 years as manager of the salt fields at Dry Creek. Other notable positions and recognition include: Colombo Plan Adviser on salt to the Ceylon government 1964; Director, Dampier Salt Ltd 1968-79; John Lewis Gold Medal (for Exploration), Royal Geographical Society of Australasia (SA Branch) 1984; Australian Geographic Adventurer of the Year 1990; President, Royal Geographical Society of Australasia SA Branch 1959-61; SA Chairman, Water Research Foundation of Australia 1961-76; President, Conservation Council of SA 1971-75; President of the National Trust of SA 1971-76; and President, Council of the National Parks Foundation of SA 1985-89.

In 1966, at the age of 50, Warren retired from industry, following his passions for conservation and bushwalking. His first long walk in the Flinders Ranges was in 1967-68 and his book Walking the Flinders Ranges is a marvelous must-read. As well as bringing back memories for those of us who are fortunate enough to have walked the Trail, it extends the experience by sharing what it was like to do it 3o years ago, without the high-tech backpacks and boots that we are blessed with today – not to mention the super-duper light-weight retractable walking poles that some of us wouldn’t be without! In contrast to this, Warren walked with a lily stem for 20 years. Well – a yacca stick, which is from the family Liliacreae, making it literally a dried lily stem:

“It is an amazing stick, and I have grown sentimentally attached to it, for it has lasted right through the Flinders walk, and subsequently through another from Kathmandu to the foot of Mount Everest.”

While my much more recent experience of walking the Trail included bus rides back to a cosy cabin or hotel room at the end of the day, Warren found other ways to keep the elements at bay. He writes of a night in the northern Flinders:

“A cold breeze was blowing down the valley as we went to bed at midnight, and since I had set down my sleeping bag in the exposed creek bed I lay with my head poked into a box turned on its side.”

On another occasion he writes of spending a night in the Aroona Hut, which was badly run down and with only one room roughly re-roofed after a gale had previously torn off the roof:

“The rain came in successively heavier showers of longer duration, but in the lulls, we ran out and collected firewood from trees in the creek. We would clearly be there for the night so we brought in masses of leaves for underbedding on the hard floor. Then in the rubbish dump I found the wire mattress of an old iron bedstead and, after propping it on stones, bending back the more dangerous of the protruding broken wire ends and padding it with wet gum leaves, I had myself set up royally.”

Warren reminds us that the Flinders is an unpredictable place and writes of the contrast of the raging day-time heat (while carrying over 60-pounds in his pack) with the rapid changes of weather, when thunder storms can suddenly appear out of nowhere:

“At noon we stopped for lunch in the gorge where Bunyeroo Creek has cut through the ABC Range, sitting amongst the long roots, and under the shelter of a large gum at the foot of the north wall. Haze and unidentifiable cloud now obscured the whole sky, and it was 96 degrees F. We drank most of our water and turned for home. … Although the dust continued to thicken the air cooled a little, and increasing thunder over the main range to the west soon became one continuous loud roll … A great menacing “red darkness” closed in until it was like dusk, or as in a total eclipse of the sun. At such times the birds and animals are said to react with cries of fear, and I imagined that the sounds of the galahs and other birds heard above the wind and thunder were, in fact, frenzied cries of fear. It was indeed awe-inspiring.”

Warren’s descriptions of the many moods of the Flinders, and their soul-deep effect on walkers, brings back so many wonderful memories:

“I had stopped to rest in the creek in the shade of a grand old gum-tree and as I lay back on the flat pebbles I suddenly perceived above me the arresting picture of the dappled grey and white bark of the tree-fork caught in the afternoon sun and contrasting with the azure sky. Temporary physical exhaustion often seems to enhance mental perception, and the simple sight struck certain chords in me, transforming the brief glimpse into a moment of truth, when suddenly I was at one with the universe. Unimportant events like this often print a bright picture that keeps coming back again and again during one’s life.”

C Warren Bonython has set out on adventures that most of us have only dreamed of. He is truly an inspiration for us to get out there and experience the wonders of the wilderness. These days, now in his early 90s, he spends his time closer to home, enjoying a more gentle pace at Romalo House in Magill with Bunty and Minnie, their beautiful Keeshond (Dutch Barge Dog), surrounded by memories of a rich and varied life. Minnie’s aqua-coloured collar and lead lie on a low cabinet in the entrance hall, next to a bust of Warren by well-known sculptor John Dowie, a pebble from Mambray Creek, and a framed photograph and poignant poem in memory of Everest mountaineer George Leigh Mallory (1886-1924), who lost his life on the mountain. Included at the beginning of the poem, ‘Finding Mallory’ by Judith Dye, is a quote from Mallory: “To refuse the adventure is to run the risk of drying up like a pea in its shell.”

In an article published in the Trailwalker in August 1999 as one of a series that featured Honorary Members of the Friends of the Heysen Trail, Jamie Shephard wrote of Warren: “As our Patron for some years we salute his foresight and adventurous spirit, as his actions have given thousands of people much pleasure and enjoyment.” I couldn’t agree more.