The three remaining members of the eleven walkers who set out from Cape Jervis to walk the Heysen Trail to Mount Babbage, now three and a half years ago, were now just ten walking days from reaching that goal. None of us had ever seen Mount Babbage at the northern tip of the Flinders Ranges but Mount Babbage had been dominant in our thinking since setting out from Cape Jervis.

We could have spent the rest of the day on the summit, reminiscing on the shared effort of the 2,000 kilometres of walking over 80 days.

Planning the route and logistics for this final stage had been particularly difficult. The 1:50,000 topographical map series ends with the Yudnamutana map and the 1:250,000 series covering the northern tip of the Ranges are of little value in planning routes and identifying and finding likely water points.

Warren Bonython’s ‘Walking the Flinders Ranges’ was heavily relied on to plan this final stage. We intended to follow much of his 1968 route north of Arkaroola. That is until we met Arkaroola’s Information Officer Lorraine Edmunds. Whilst Dick Grant and I were filling our vehicle with fuel at Arkaroola’s public fuel bowsers soon after arrival on the afternoon of Friday 17 October 1986 we asked the attendant what he knew of the current water situation in the ranges to the north. ‘Not much’ was the reply followed by the helpful suggestion we seek out and talk to Lorraine Edmunds in the Arkaroola Information Centre. This quickly proved to be an invaluable suggestion.

We found Lorraine busily at work at the Information Centre and she very kindly offered to meet with us at her staff flat that evening.

Bob Nicolle and his family arrived soon after and after establishing our camping arrangements in the Arkaroola Caravan Park we went to Lorraine’s flat to gain as much knowledge of the current conditions to the north as she was able to provide. After explaining our proposed route to Mount Babbage and the areas where we were uncertain of the availability of water, Lorraine asked why we had not chosen to include the Mawson Plateau in our route. ‘Where’s that’ we asked. For the next hour we sat enthralled as Lorraine described the area north of Freeling Heights, showing us photographs she had taken during her visits to the plateau, and identified the plateau on our 1:50,000 Yudnamutana map. We immediately changed that part of our planned route to incorporate crossing the Mawson Plateau.

At 8.00 am the following morning, following the mandatory photographs taken by Bob’s wife Maureen, we left from the front of the Arkaroola complex and followed a station track to the south-east. About mid-morning, as we neared Frome Lookout, we left our packs and walked south to the summit of Mount Warren-Hastings (~ 590 metres). The weather was fine and warm and from the summit we obtained splendid views of the Gammon Plateau, and particularly Benbonyathe Hill. After returning to our packs we continued to follow the track to Frome Lookout (~ 420 metres) where we had lunch whilst taking in the excellent view of Humanity Seat. After lunch we left the track and headed east and then north-east, crossing the Arkaroola entrance road before following a creek downstream through Kingmill Gorge to its junction with Arkaroola Creek.

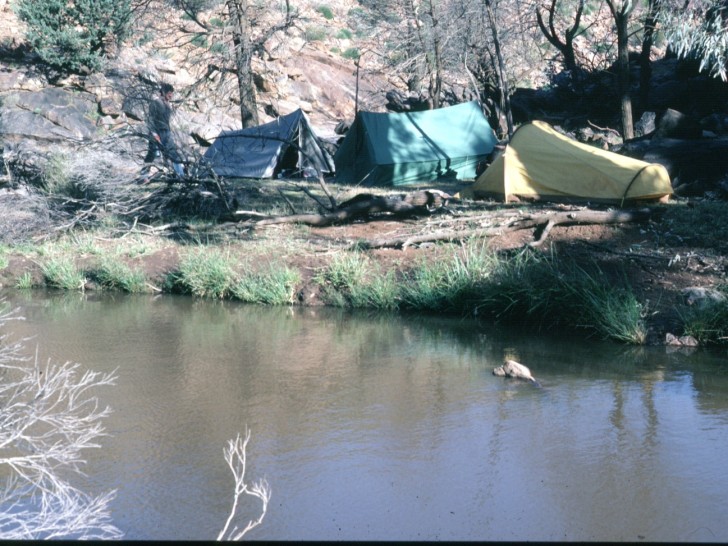

At the junction we again left our packs and followed Arkaroola Creek downstream for a kilometre to the spectacular Tillite Gorge. After returning to our packs we proceeded upstream along Arkaroola Creek. In the late afternoon an attractive campsite was selected on the banks of the creek between Stubbs Waterhole and Barraranna Waterhole. Our campsite was enclosed by sheer rock walls on both sides of the creek and as light faded we were entertained by amazing lighting effects on the walls.

Reaching Barraranna Waterhole was our first objective the next morning as we continued upstream along Arkaroola Creek. In a short time we reached the waterhole. The amount of water and the sheer rock walls around the waterhole prevented walking further upstream along Arkaroola Creek so we left the creek and walked west and then north through Spotted Schist Pass and arrived back at Arkaroola Creek two kilometres upstream of Barraranna Waterhole.

Soon after reaching Arkaroola Creek we again left our packs and, by following a tributary, headed to the north towards Humanity Seat. From the headwaters of the tributary it was only a short walk to the summit of Humanity Seat (655 metres). We spent half an hour admiring the view, to the east over the plain towards Lake Frome, and to the north were our journey lay in the days ahead. A different route was taken back to our packs. We remained on the high ridges leading us to the south for as long as possible before dropping down to our packs at Arkaroola Creek.

Following lunch a midday lunch we continued upstream along Arkaroola Creek, past Mundoo Dopinna Waterhole. On reaching Echo Camp in the mid-afternoon we selected an attractive campsite and Dick and I climbed nearby Dinnertime Hill (~ 540 metres). On returning to the campsite we found Bob had been joined by his family who stayed with us for tea. Although we had left Arkaroola two days earlier we had only progressed three kilometres north of the latitude of Arkaroola. In fact we were still south of the most northerly point we had reached on the previous stage.

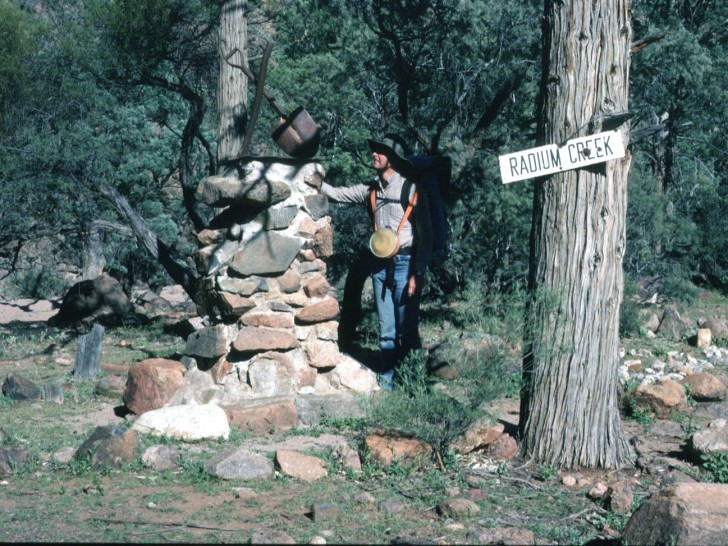

But that all changed the next morning as we headed north along Arkaroola Creek, soon coming to its junction with Radium Creek which we followed upstream through American Gap and Sunshine Pound. Occasionally we observed the remnants of a mining track that had been constructed along the creek bed, now being progressively obliterated by infrequent flood events.

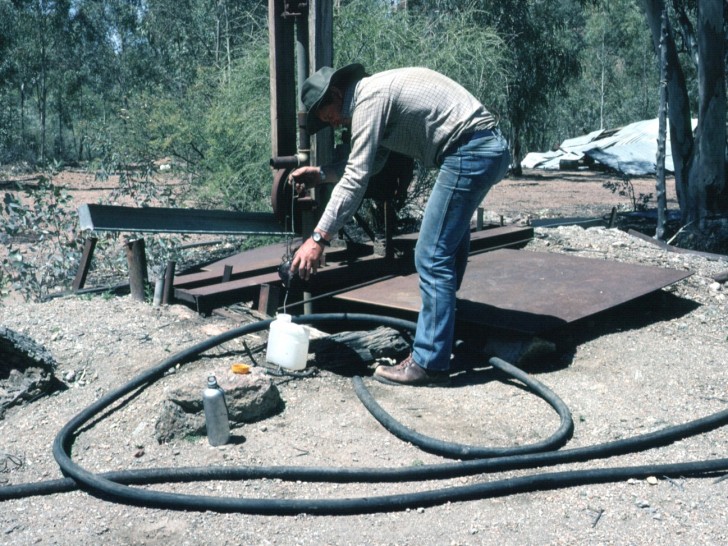

After crossing the Ridgetop Track we continued up Radium Creek to East Painter Bore and the abandoned Mount Painter Mine Camp site. Obtaining regular water supplies was going to be the key to the success of this walk. East Painter Bore is one of the few reliable sources of water in the area, even though obtaining it was a slow and laborious task using a billy lowered into the bore hole at the end of a length of rope.

Mid-morning we headed east up a steep track. As we gained height the full extent of the tracks and drilling platforms associated with the uranium exploration program in the area in the 1960s was revealed. Whole hillsides were a maze of earthworks and the tremendous effort required to position huge drilling rigs on precipitous slopes was difficult to fully comprehend.

Skirting around the southern flank of Mount Gee we diverted off the track and followed a creek to Mount Gee waterfall where we stopped for lunch. Seeing numerous exposed quartz crystals, literally components of all of the rocks in the area, was an amazing experience.

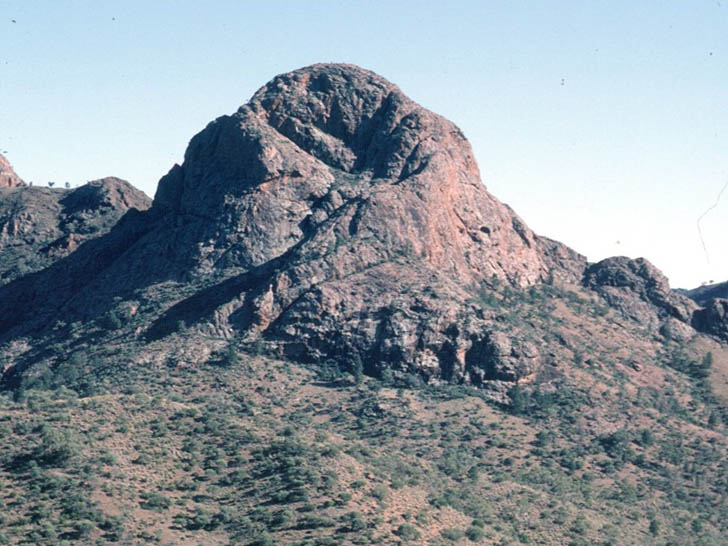

After lunch we selected an attractive campsite on a sand bank at the base of the waterfall and set out to climb Mount Painter. As we neared the summit by following an undulating but steadily rising ridge my thoughts turned to our first sighting of Mount Painter, from our campsite on Aroona Bluff at the western end of the Gammon Plateau, eight walking days earlier, when it was strikingly illuminated at sunrise.

The view from the summit of Mount Painter (~ 790 metres) was excellent and we spent some time identifying those places to the south we had already visited and those places to the north and north-west we would visit in the coming days. Particular attention was given to assessing our proposed route to the summit of The Armchair the following day.

Mid-afternoon we commenced our descent and arrived at the Ridgetop Track at the same time a group of tourists on Arkaroola’s four wheel drive Ridgetop Tour stopped above the Mount Gee waterfall whilst on their return from Sillers Lookout.

Whilst Dick returned to our campsite Bob and I quickly scrambled up a rocky slope to the summit of Mount Gee (640 metres). From the summit we gained an even greater appreciation of the 1960s exploration effort and the setting sun in the late afternoon created wonderful shadow effects on mountainous terrain. We returned to our campsite well satisfied with the day’s northwards progress.

We left our campsite just after 7.00 am the following morning, heading north along a steadily rising creek bed until we reached a saddle at the head of the creek and then descended to Armchair Creek. At Armchair Creek, after a short rest, we left our packs and commenced the ascent of The Armchair. Following the route we had identified the previous day we walked west to the entrance of the scree valley that leads up onto the ‘seat’ of The Armchair. We then scrambled up the left hand ‘arm’ and onto the dome. Some spots during the ascent were quite exposed but we reached the summit (~ 720 metres) with ease, relative to our expectations. When we encountered the Ridgetop Tour Group the previous afternoon above the Mount Gee waterfall it was arranged with the tour guides that we would signal the following morning’s Ridgetop Tour group when they reached Sillers Lookout using a heliographic mirror that had been lent to us by Doug Sprigg prior to our leaving Arkaroola. We had also arranged that the tour guides would respond with mirrors.

Whilst on the summit of The Armchair which coincided with the arrival of the morning Ridgetop Tour at Sillers Lookout two way mirror contact was made quite easily. A short time later the Arkaroola plane was sighted out to the west, flying north. As the plane circled to the south we signalled the plane and it diverted towards The Armchair, flying past us at distance of just a few hundred metres. With Mount Painter in the background I took a photograph of the plane as it flew past. There was a tense few minutes as we left the summit because it was important to accurately retrace our steps off of the dome. Without care it would have been all too easy to descent in the wrong direction and end up on the very steep and dangerous slopes that are a feature of most of The Armchair.

After returning to our packs we followed Armchair Creek downstream for several kilometres before diverting up a tributary to the east to intersect with the Ridgetop Track. A very steep walk up the Track brought us to a ridge near Mount Ward where had lunch whilst enjoying great views of The Armchair and the deep chasm that was Yudnamutana Gorge looming to our north. Continuing to follow the Ridgetop Track we reached Sillers Lookout just prior to the arrival of that afternoon’s Ridgetop Tour. To our amazement we learnt that some of the people on the Tour were on the plane that flew past us whilst on the summit of The Armchair that morning – and that they had photographed us from the plane as I had photographed the plane. An exchange of addresses lead to an exchange of copies of the respective photographs.

After four days of near solitude it was a strange feeling to be surrounded by thirty tourists and we soon decided to move on. We left Sillers Lookout by way of a very steep and badly eroded track down to Yudnamutana Creek and established our campsite just upstream of the junction of the track and the creek. At just 230 metres above sea level this was the lowest campsite since camping at the base of Mount Cavern near the junction of Mambray Creek and Alligator Creek during Stage Four. As we had arrived at our campsite a little earlier than planned and the temperature was quite warm Bob and Dick decided to walk up the Creek into Yudnamutana Gorge to seek out a rock pool suitable for bathing. I elected to explore some of the numerous exploration tracks and drilling platforms that had also been constructed in this area.

That night turned out to be one of the most memorable of the entire walk. Just after dark an enormous gully wind came rushing down the gorge. For seemingly hours, with river sand swirling around and through the tent, I clung to the poles of my tent to stop it collapsing.

Despite the blustery night we woke to a calm morning and leaving our campsite intact we left early to walk to Paralana Hot Springs. After walking north-east, downstream along the banks of the Yudnamutana Creek downstream for nearly five kilometres we reached the Paralana Hot Springs on Hot Springs Creek. Our purpose for visiting the Hot Springs was twofold. To view the springs and to meet Maureen and her boys who had our mid stage food re-supply. Maureen and the boys arrived shortly after us and we stayed an hour inspecting the springs and Arkaroola’s nearby abandoned vineyard venture.

On return to our campsite we quickly cleaned our sand impregnated equipment and packed our new food supply before heading upstream into Yudnamutana Gorge.

Discussion when we stopped for lunch an hour later centred on our water strategy for the next two days. Water was available in increasingly irregular pools in Yudnamutana Creek. Lorraine Edmunds had assured us water would be plentiful on the Mawson Plateau but we had to decide when to pick up water for the one and a half days until we reached the plateau.

Soon after lunch we reached the junction of Yudnamutana Creek and Armchair Creek. Leaving our packs we followed Armchair Creek upstream to its junction with Commonwealth Mine Creek. A short distance further up Armchair Creek we reached a substantial waterfall and we spent some time scrambling over the rocks that formed the waterfall.

On returning to our packs we continued following Yudnamutana Creek upstream. The pools of water were becoming less frequent, and we decided it was time ‘fill up’. We did, in fact, manage to ‘fill-up’ at the last available pool of good quality water.

In the mid-afternoon we left the Yudnamutana Creek and commenced following Junction Creek upstream to the north. After several kilometres we reached the Wind Funnel, so named by Warren Bonython in 1968. This short rocky gorge contained water of doubtful quality. The extent of the pool of water necessitated a difficult detour high up to the left of the gorge and it took some time to regain the bed of the creek and continue our journey north. In the late afternoon we selected a campsite just south of Stanley Mine. Our map showed a number of historic mine sites in the immediate vicinity and we speculated about the early occupant of a ruined cottage near our campsite.

We set off without packs early the following morning. Our first objective was to climb Willigan Hill several kilometres north-west of our campsite. We spent some time on the summit (669 metres), looking at the myriad of rolling hills to the north and the west as well as the route we were to take to the east to Freeling Heights later in the day. Returning past our campsite we retraced part of our steps from the previous day before diverting to the east to climb Mount MacDonnell. We decided to climb this peak because there was confusion about its precise location. The presumed position of Mount MacDonnell is indicated on the First Edition 1:50,000 Yudnamutana map we were carrying but we had heard there was doubt if the position indicated on the map was correct. A steep climb brought us to the location of Mount MacDonnell (~ 820 metres) as indicated on our map. No cairn of trig point could be found, which we considered unusual for a named peak, giving weight to the possibility that Mount MacDonnell was in fact one of the other nearby peaks, all of which were about the same height of the peak we were on.

After hurrying back to our campsite, packing and consuming a quick lunch we walked east, passing more historic mine sites. Our campsite that evening had to be on water on the Mawson Plateau and we planned to get there by way of Freeling Heights. After passing over a watershed we entered the headwaters of north flowing MacDonnell Creek. A steady climb brought us onto the relatively flat Freeling Heights and we soon reached the summit (944 metres), marked by a substantial cairn.

The views east and south over Hot Springs Creek were magnificent. We also gained our first glimpse north over the Mawson Plateau. A campsite with water that night was now down to Lorraine Edmunds.

Because we were anxious to confirm the availability of water, we soon started onto the Plateau. A steep drop of 250 metres brought us down onto the Plateau. It was quickly apparent the country was different. The terrain was flat and softer and the type and appearance of the vegetation differed markedly. To our relief we soon came across the first pool of water.

An hour and a half after leaving Freeling Heights we came across the first evidence of the granite wonderland that Lorraine had described. A series of waterfalls with a steady flow of cascading water and a nearby grassy flat provided a stunning campsite.

We intended to follow this creek across the Mawson Plateau and onto its junction with Hamilton Creek. We set of the next morning in high spirits. To be prudent we had filled all of our water containers and were now assured of water all the way to Mount Babbage. Lorraine’s description of what we were to experience on the Mawson Plateau had already, in a short time the previous day, exceeded our expectations.

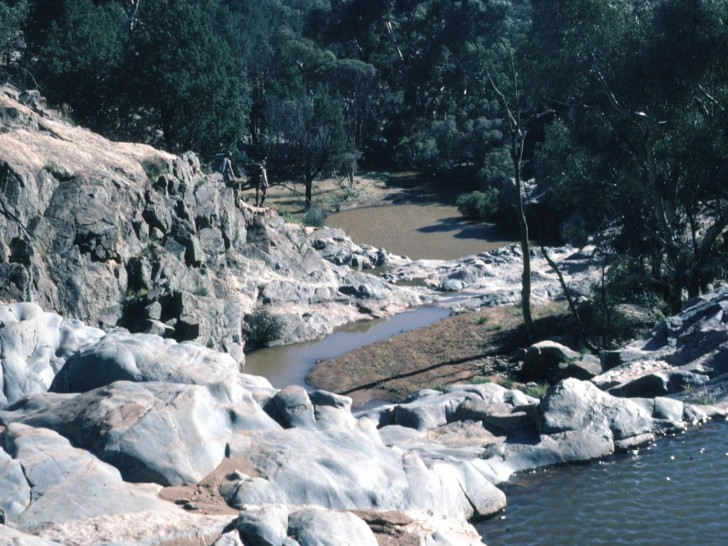

As we walked downstream the granite created landscapes entirely different from anywhere else in the Flinders Ranges. At every turn we marvelled at the waterfalls, deep tree-lined waterholes, and long continuous stretches of water. We could hardly contemplate that we were at the arid northern tip of the Flinders Ranges.

Frequent stops to take in the magnificent scenery contributed to slow progress, and some sections, choked with huge boulders, made walking with our heavy water-laden packs arduous. Our walk across the plateau ended at lunch time when the area took on a more typical Flinders Ranges appearance and water was no longer present. It was mid-afternoon when we emerged from a narrow gorge the creek had become and an hour later we selected an attractive campsite on a sandy bank adjacent to the creek.

We were now right on the upper edge of the 1:50,000 Yudnamutana map and soon after setting out early the next morning, continuing to follow the north-flowing creek downstream, we entered the remaining stage of the walk where we had to rely on the 1:250,000 Callabonna and Frome maps. It quickly became apparent that I now needed to pay even closer attention to navigating our way. By mid-morning we reached the junction of the creek we had been following for the past day and a half with Hamilton Creek.

We left our packs and walked to the west, upstream along Hamilton Creek for nearly six kilometres, to the base of Mount Livingstone. A 300 metre ascent from the bed of Hamilton Creek brought us to what we understood from our map was the summit of Mount Livingstone (635 metres). However the lack of a cairn or any type of marker on the summit gave us doubt. In climbing Mount Livingstone we had re-entered the area covered by the 1:50,000 Yudnamutana map and we were confident we were at the point on the map indicated to be Mount Livingstone. Interestingly the second edition 1:50,000 Yudnamutana map I subsequently obtained for a later Mawson Plateau walk does not identify the location as Mount Livingstone. In fact the second edition map did not refer to a Mount Livingstone at all. (The second edition map did have Mount MacDonnell in the same location as the first edition.)

After returning to our packs, which was also our lunch spot, we commenced following Hamilton Creek downstream. The creek started to broaden out. At our campsite in the bed of the creek later that afternoon we estimated the creek was three kilometres wide.

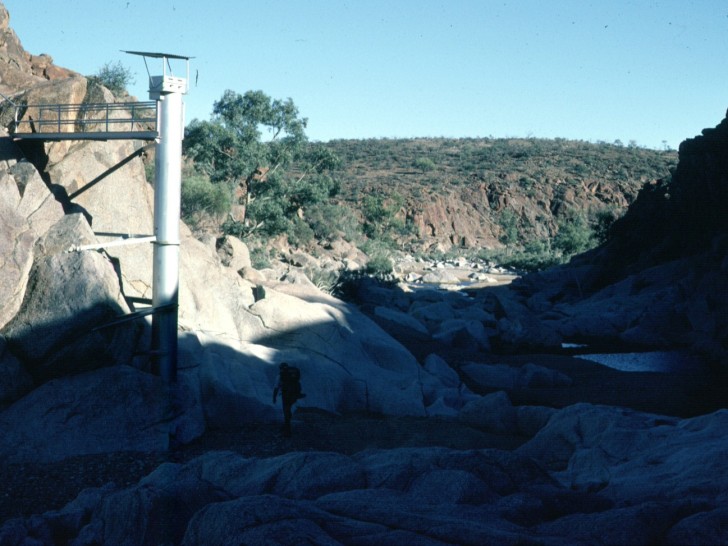

We set off the next morning with a sense of anticipation. Within few hours we expected our first glimpse of Mount Babbage. The Hamilton Creek commenced to narrow and soon after we passed through the two narrow gorges that comprise Brindana Gorge. Perched high on the right-hand side of the second gorge was an enclosed observation platform, established for observing the numerous, but shy, Yellow Footed Rock Wallabies that frequented the gorges. As we emerged from the second gorge we enjoyed our first view of the flat mesa top of Mount Babbage, about ten kilometres to the north-east.

After passing through Brindana Gorge the Hamilton Creek commenced a meandering path through undulating country. Leaving the creek we walked east for several kilometres and left our packs to climb Parabarana Hill. At least that was the plan! For just the second time in the whole of the estimated 2,000 kilometre walk I, temporarily, misplaced myself and my companions. As a result of the challenge of the transition from a 1:50,000 map to a 1:250,000 map, and perhaps also overconfidence, we walked in a more southerly direction than intended, and ended up walking towards Mount Neil.

Fortunately I discovered my error before we had gone too far and we re-traced our steps for several kilometres before walking east to the summit of Parabarana Hill (311 metres), arriving an hour late. Mount Babbage now stood out clearly, just nine kilometres to the north. Seeing Mount Babbage, now less than half a day’s walk away made up somewhat for my error.

After returning to our packs we followed a creek downstream to its junction with the Hamilton Creek where we established our final campsite. The next morning we would reach Mount Babbage. There was great expectation and pride in what we had achieved. As a result of the navigation error the previous afternoon we left our campsite before 7.00 am the following morning, walking north down the sandy bed of the Hamilton Creek, avoiding the many saline pools of water that were a feature of that part of the creek.

After an hour we entered another rocky gorge and passed a large metal structure extending into the creek bed, installed by the Engineering and Water Supply Department for the purpose of measuring the enormous flood waters that must flow down the Hamilton Creek from time to time. Soon after we arrived at Terrapinna Waterhole, the most northern and most likely the largest waterhole in the Flinders Ranges. Some time was spent in negotiating around the left-hand side of the waterhole. By mid-morning we had reached the northern end of the waterhole and emerged from the gorge.

Mount Babbage was now prominent, just several kilometres away.

Leaving our packs where the Lyndhurst to Moolawatana track crossed the Hamilton Creek we quickly set off for the summit. In addition to some food, water and cameras we also carried our Jubilee 150 flag, carried all the way from Cape Jervis.

Reaching the summit of Mount Babbage was an easy walk, much different from most of the seventy peaks we had visited since leaving Cape Jervis three and a half years before. As we neared the summit my mind was full of the journey the brought us here. And then we were on the summit (300 metres). It was Monday 27 October 1986.

Bob, Dick and I shared congratulations all round. We could have spent the rest of the day on the summit, reminiscing on the shared effort of the 2,000 kilometres of walking over 80 days. However our planned rendezvous with Maureen Nicolle on the track near Terrapinna Waterhole for transport back to Arkaroola meant we stayed for just an hour.

We arrived back at our packs just as Maureen and her boys arrived.

Jump to content:

- Introduction – The First End-to-End walk of the Heysen Trail

- Stage One – Cape Jervis to Cudlee Creek

- Stage Two – Cudlee Creek to Burra

- Stage Three – Burra to Melrose

- Stage Four – Melrose to Kanyaka Ruins

- Stage Five – Kanyaka Ruins to Aroona Hut

- Stage Six – Aroona Hut to Sliding Rock Mine

- Stage Seven – Sliding Rock Mine to Arkaroola

- Stage Eight – Arkaroola to Mount Babbage